Memories Editorials #2 Thinking slow and fast: a mathematical justification for the need for an archive

This article talks about a text that is usually at the top of the “books that change your life” lists. Thus, think about it before you continue: your life may be different after this experience, and not necessarily for the better!

Yet, the point is, at least from our perspective, to remember it well.

The book in concern is Thinking, fast and slow by Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel Prize-winning author for his research on behavioral economics. We even mentioned him in our first editorial, and we liked the idea of taking a closer look at his work.

System 1 and System 2

This is Kahneman’s idea: the human mind works in two modes of thought: one is quick and instinctive (fast thinking, system 1); the other is more meditative and analytical (slow thinking, system 2).

- System 1 represents our automatic, instinctive way of thinking that helps us make quick decisions without too much hesitation.

- System 2 represents, instead, our more rational, logical, and conscious way of thinking. It is our analytical mind and requires a greater cognitive effort.These two modes of thought can affect our decisions, causing judgment errors and cognitive bias, leading us to misunderstand our relationship with reality.

The bias we shall focus on is that which Kahneman defines as the “tyranny of the remembering self”. For the sake of practicality, we shall call it “time bias” or “contemporaneity bias”: namely, our tendency to give more importance to recent events than past events.

The colonization of pain

Tastes and decisions are forged by memories, and memories are nearly always wrong.

According to Kahneman, time bias is caused by a conflict between experience and memory.

To prove this, the author resorts to a method that is as creative as it is sadistic: an experiment to measure the pain of unaware patients during their colonoscopies (if you find this inappropriate or vulgar, keep in mind that this story ends with the awarding of a Nobel Prize).

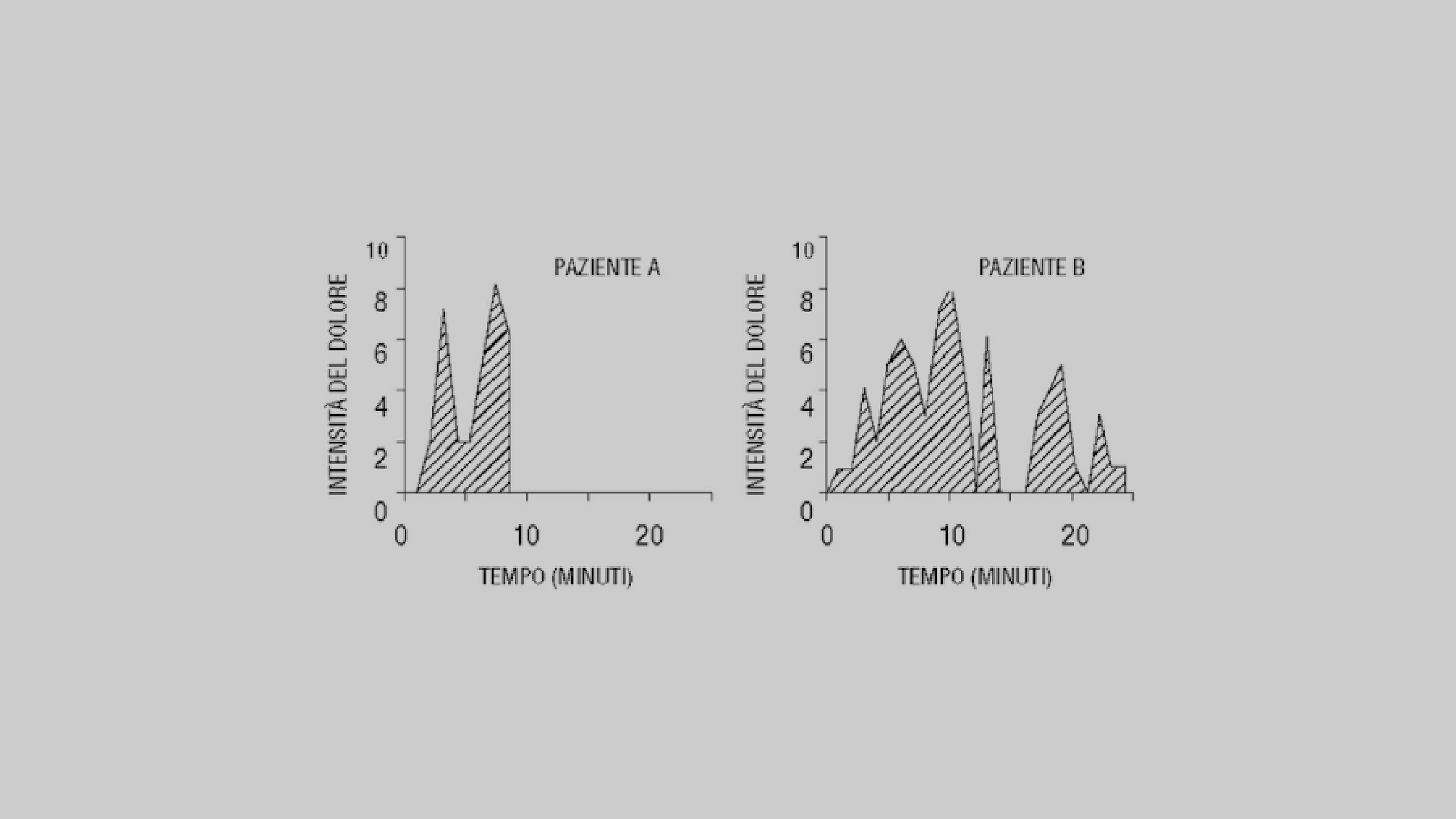

By using an instrument ironically called hedonimeter, Kahneman measured the pain felt by the patients during the test moment by moment and illustrated it in the following graphs.

Conclusions:

The first procedure lasted less than ten minutes and ended with a peak of pain.

The second procedure lasted longer and caused prolonged pain, but ended with a more tolerable moment of pain.

The “quantity of pain” applied in the second procedure was greater, although patient A’s “experienced pain” assessment was higher than that of patient B. This may derive from two aspects:

- The peak-end rule: the overall assessment of an experience is always affected by its final moment or worst moment.

- Negligence of the duration: the time of an experience has a limited effect on its overall assessment.

In short, a significant difference between the moment-by-moment pain and the remembered pain was recorded. Why? Because, through our memories, we reassess real-life experiences. We do it by giving more importance to the peaks of pain and how the experiences ended.

Confusing an experience with the memory of an experience is an inexorable cognitive bias […] The experiencing self has no say. The remembering self makes mistakes, at times, but is the one who keeps score, manages whatever we learn in life, and makes decisions […] This is the tyranny of the remembering self.

Lack of integral-ism

But why do our minds fool us like this?

According to Kahneman, it is because they are not designed to calculate integrals. Integrals? Yes, they have a lot to do with this topic, although it took us some time to understand it.

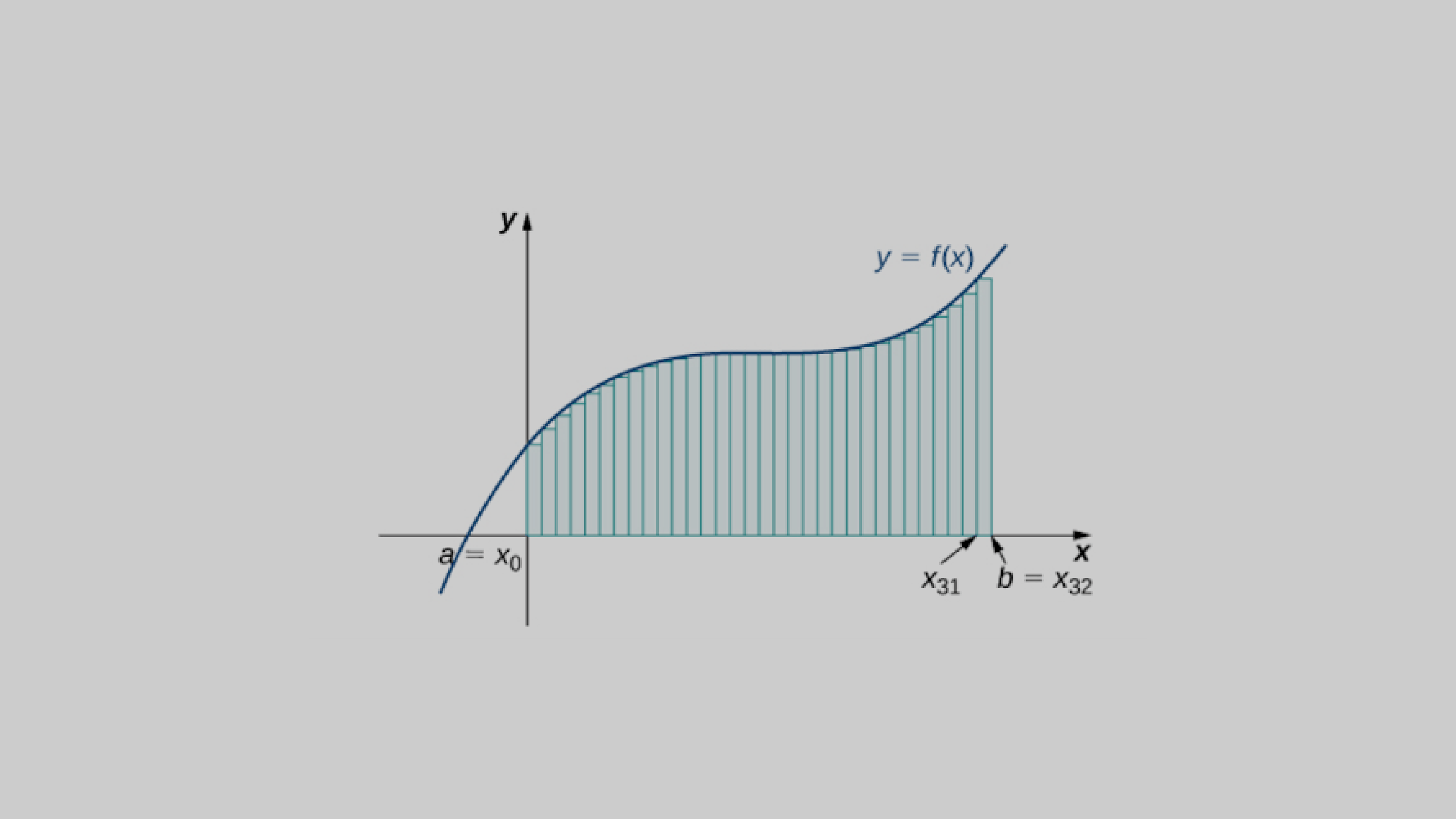

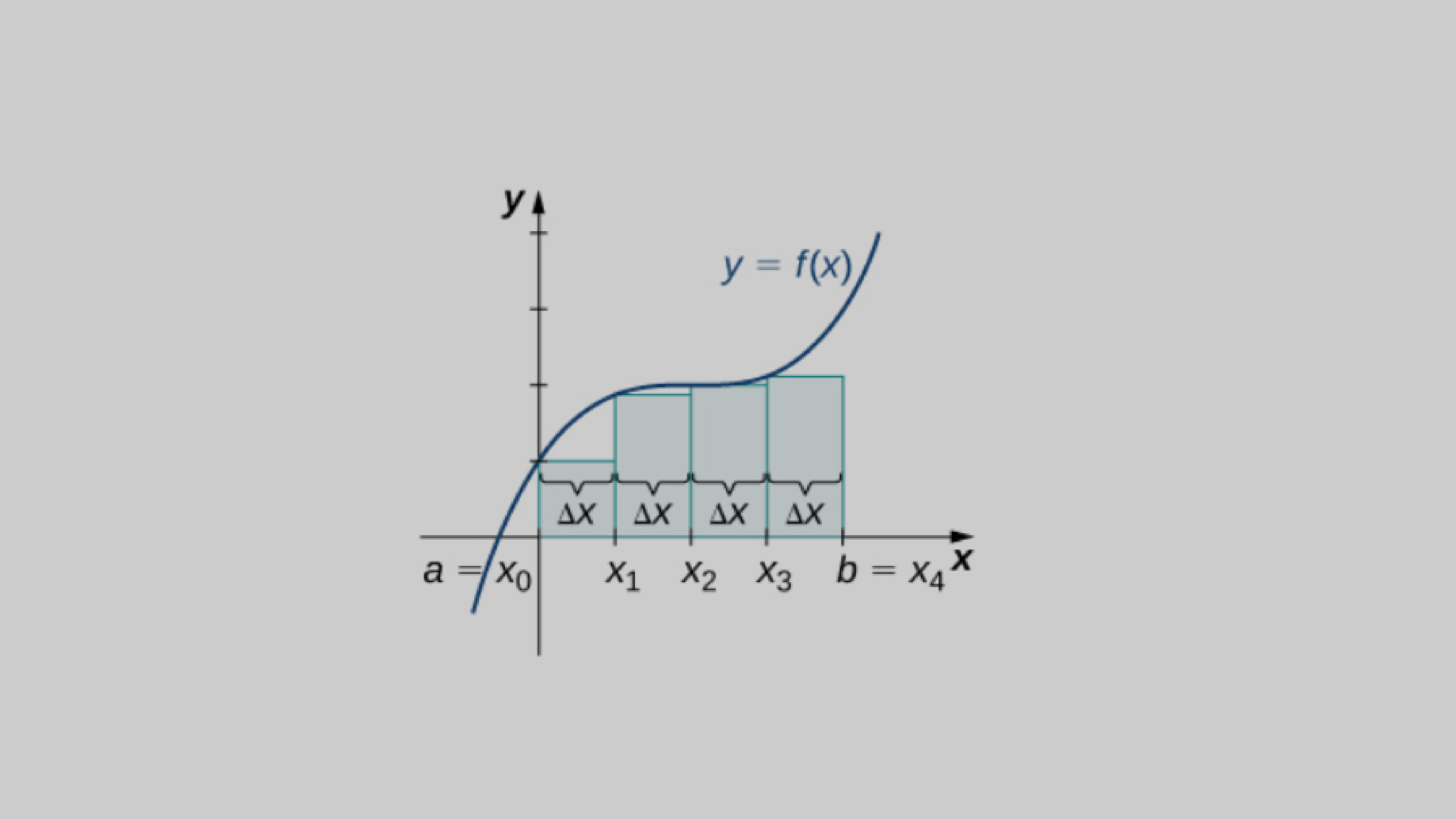

As far as we understood, to measure the area under a curve, we would have to sum the areas of all the rectangles constructed under it, as in the figure below. Yet, to have an exact result, the rectangles would have to be so small as to be essentially invisible.

Now, if we try to see reality as the blue curve and the light blue rectangles as “blocks of time to remember”, we can say that our memory fails to build sufficiently small blocks. We forget individual moments and we remember larger, blurrier blocks.

Therefore

Why is it so difficult to make someone understand that they need an archive?

Because, within an archive, time is processed differently. The archive can “integrate” its contents in time categories where relevance is not determined by peaks, but by temporality itself.

The human memory in its most instinctive form does not work this way. This is why you need to use and develop a more rational and analytical memory to perceive the need for an archive. Once you do, you will be able to see the story more clearly, without the flashy conclusions that decorate your recollections. You will remember when you truly felt pain, when you succeeded or were just lucky, and if the doctor really tricked you that time to win the Nobel Prize.

Stefano Trinchero

Chief Data Scientist at Promemoria Group

Credits

The cover image is by Tony Cenicola/The New York Times.